BRISBANE, AUSTRALIA: As the world marked the 25th

anniversary of freedom returning to Eastern Europe, it is sad that two of the

wisest post-communisleaders are no longer with us.

In the extraordinary events

that followed the collapse of the Berlin Wall, Poland was the inspiration. It

had elected a non-communist government months before the wall came down. Lech

Walesa, Pope John Paul II are true heroes who changed the world. Ronald

Reagan’s strong stance and his 1987 call to “tear down this wall” were

similarly decisive. Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader-- still alive at

83—courageously allowed the wall to be opened, sacrificing in the process

Moscow’s loyalist East German communists.

Comprehending the enormity of

Gorbachev’s deed, an astonished British editorialist wrote that, “all of Stalin’s

war time territorial gains in Europe were given up without a shot being fired.”

Events cascaded rapidly.

Czechoslovakia’s communist government collapsed within days after the wall came

down. Hungary catapulted towards free elections while the remaining regimes--

Romania, Bulgaria and Albania-- toppled like a row of dominoes. In 1990 East Germans voted to merge

their country with West Germany. And late in 1991 the USSR itself collapsed,

fragmenting into 15 separate countries.

History, in my opinion, will

judge Vaclav Havel of the Czech Republic and Lennart Meri of Estonia the most

significant leaders to have emerged from the wreckage of communism.

Meri, Estonia’s president from

1992 to 2001, deserves recognition. Born into a prominent family, when the Red

Army invaded in 1940, 12 year-old Meri, his mother and younger brother were exiled

via prison train to the Siberian gulags. His father, an Estonian diplomat, had

to endure Moscow’s infamous Lubyanka prison. Miraculously the family survived

and later Lennart was permitted to attend university. He became a respected

writer and filmmaker. He was 60 when the Wall came down.

Meri earned the admiration of

Estonians during the failed coup against Gorbachev in August 1991. With his

countrymen terrified that a Russian invasion would soon snuff out their drive for

independence, Meri took to the radio, assuring citizens they needn’t worry,

that he knew the plotters to be clueless and incompetent. There was no invasion

and Meri’s grandfatherly counsel had enormous impact.

Fluent in six languages, most

learned as a youth during his father’s postings abroad, Meri repeatedly

observed that the end of communism was a beginning, not an end. A tall,

dignified man, Meri understood the horror of mass deportation. But remarkably

he championed the cause of freedom for Russians. He died in 2006. Were he alive

today Meri would be aghast at Russian actions in Ukraine, and equally comforted

that Estonia’s security is anchored in Nato and European Union membership.

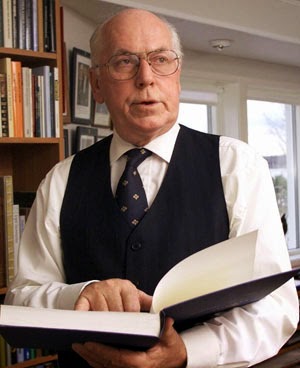

Lennart Meri as president

Vaclav Havel, like Meri, for

five decades was deprived of the honest, authentic life he so passionately

wanted. Like tens of thousands, he had to make the best of a bad situation.

Like Meri, Havel paid a heavy price for coming from an entrepreneurial

family that after the communist takeover in 1948 was denounced as a class enemy.

Coming of age during the period of maximum repression, he was banned from

universities. In 1975 he wrote a

devastating critique of totalitarianism. In six pages Havel dissected the

massive fraud and corruption of communism. Its lofty ideals, he wrote, were

hollow.

Reflecting on the 1989 Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia, Havel

explained to an audience at the World Economic Forum in 1992 how Soviet

imperialism imploded.

"Communism was not defeated

by military force, but by life, by the human spirit, by conscience…. It was defeated

by a revolt of color, authenticity,.. and human individuality."

Famous for his essay on the power of the powerless, Havel lived to see

the society where imperfectly, “truth and love prevail over hate and lies.”

Vaclav Havel

Universally hailed as a great European, Havel the dissident playwright

spent years in communist jails before being swept to the Prague Castle in the

Velvet Revolution. He served as president first of Czechoslovakia and then the

Czech Republic from 1989 to until 2003.

Vaclav Havel died at age 75 in 2011. Writer Anne Applebaum hails Havel’s unique success in making

the transition from dissident to national leader.

Alan Levy, the founding editor of the Prague Post, was asked why Prague

had become the in spot for émigré young Americans in the 1990s. He replied that

he himself had pondered the question, why Prague instead of Berlin, the place

that exemplified both the wall and freedom. “Prague,” he concluded, “became the

Mecca for young people because of one man, Vaclav Havel. It was Havel’s example

of intelligence, modesty, artistry and love that drew people to Prague.”

Havel and Meri, I suspect, would both celebrate 25 years of freedom,

while warning of the obvious dangers ahead.

Barry D. Wood covered the collapse of communism and the rebuilding of

Eastern Europe for Voice of America. A version of this article appeared on

marketwatch.com